Egittomania / Egyptomania - parte 3

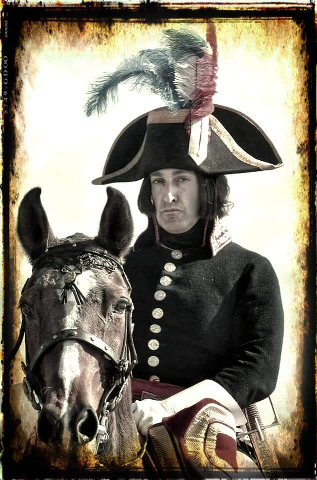

La campagnia d'Egitto di Napoleone.

Napoleone Bonaparte, convinto dell’impossibilità di uno scontro diretto con l’Inghilterra, propone al Direttorio di partire alla conquista dell’Egitto per tagliare agli inglesi la via delle Indie.

La flotta francese, che trasportava l’armée d’Orient diretta in Egitto, partì il 19 maggio 1798, portando con se anche 167 scienziati di diverse discipline e artisti.

Lo scopo di Buonaparte era quello di far realizzare loro il “grande inventario della valle del Nilo”, fino ad allora quasi conosciuto e tramandata solo dai racconti di pochi viaggiatori.

Rimandiamo ad altre pagine la storia militare della campagna d’Egitto e ci concentriamo sul risultato scientifico della spedizione che portò ad interessanti scoperte.

Il gruppo di studiosi, messi al servizio del nascente Institut d’Egypte creato a modello dell’Institut de France, vennero chiamati dai soldati Savants (scienziati), e riprodurranno con minuzia centinai di oggetti e monumenti, raccogliendo un’enorme massa di informazioni.

Nel settembre 1798, Napoleone, si reca con alcuni Savants a Giza, per osservare da vicino e scalare la grande piramide di Cheope che solo successivamente verranno studiate a fondo.

Nel novembre del 1798, Vivant Denon, incisore e scrittore (successivamente fatto barone e il primo organizzatore del Louvre) parte per l’Alto Egitto al seguito della XXI brigata del Generale Desaix; durante le brevi soste, disegna ed annota febbrilmente tutto ciò che di interessante gli si presenta; questi disegni confluiranno, nel primo trentennio dell’800, nei volumi di testo e nelle tavole della “Description de l’Egypte” che negli anni a venire verranno prese a modello per le famose ceramiche francesi di Sèvres (famoso il servizio egizio, regalo di divorzio di Napoleone a Josephine su cui erano riprodotti i paesaggi di Denon) e successivamente usati per produrre dei gioielli dal gusto orientale dai più famosi gioiellieri francesi.

L’opera, realizzata su carta speciale e formato inusuale, uscì in una prima edizione pubblicata a fascicoli tra il 1810 ed il 1826 e venne dedicata a Napoleone, tant’è che venne chiamata “Edizione Imperiale”.

Intanto la situazione militare si fa sempre più critica. Napoleone rientra segretamente in Francia nell’agosto del 1799, seguito man mano dagli scienziati dell’Institut d’Egypte.

Nella seconda metà di luglio del 1799, il Luogotenente Pierre Francoise Xavier Bouchard scopre per caso, tra il materiale di riempimento di un forte presso Rosetta, un blocco di pietra nera con incisi segni di differenti scritture del peso di 762 Kg che evidentemente era stato asportato da un edificio antico.

I francesi si rendono subito conto dell’importanza di questo oggetto, e decidono di trasferirlo all’Institut d’Egypte, dove gli esperti si interrogheranno a lungo sulle scritture che vi compaiono: la prima in alto è in geroglifico, quella centrale in demotico (una scrittura corsiva diffusasi in Egitto nel corso del VII ec. a.c.), e quella in basso in greco. La “stele di Rosetta”, come verrà poi chiamata, fu la scoperta più importante della spedizione francese, ma solo nel 1822, dopo vari tentativi da parte di diversi studiosi inglesi, Jean Francois Champollion riuscì a decifrarla, gettando le basi per la comprensione della civiltà dell’antico Egitto e lo scoppio, soprattutto in Francia, dell’egittomania. Il testo della stele fu redatto dai sacerdoti riuniti a Menfi, per celebrare l’incoronazione di Tolemeo V Epifanie (196 a.c.) e proclamarne il culto ufficiale del sovrano-dio in tutti i templi del paese.

La partenza dei Savants dall’Egitto non fu priva di difficoltà, alcuni di essi, sopravissuti alla peste, anche dopo lo sbarco degli inglesi avvenuto l’8 marzo 1801, riuscirono a partire con tutti i loro materiali il 9 agosto. Altri, invece, che si erano diretti ad Alessandria, rimasero bloccati in città per cinque mesi, ostaggi dell’avidità degli inglesi capeggiati dal Generale Hutchinson, che voleva impossessarsi di tutto il materiale raccolto dai savants considerandolo bottino di guerra, sollevando le proteste della delegazione francese composta dai naturalisti Savigny e Saint-Hilaire recatasi dal Generale per difendere il prodotto del loro lavoro.

Pur sottominaccia di essere resi prigionieri Saint-Hilaire decide di fare un ultimo tentativo concludendo il suo discorso con queste parole divenute celebri:”no, non obbediremo! Bruceremo noi stessi le nostre ricchezze. È alla celebrità che puntate. Ebbene, state certi che la storia vi ricorderà: anche voi avrete bruciato una biblioteca ad Alessandria!”.

A quel punto gli inglesi cedettero, seppur parzialmente e gli studiosi francesi furono autorizzati a portare con se solo reperti di medie dimensioni e documenti personali; furono così costretti ad abbandonare tutto il resto compresa la celebre stele di Rosetta, tuttora conservata al British Museum di Londra.

Insomma, se la spedizione d’Egitto non ha lasciato il segno nella storia militare, ha permesso di scoprire un passato… che pareva perduto.

Anna Lisa

***

Napoleon Bonaparte, convinced of the

impossibility of embarking in a direct confrontation with England, proposed to the Directory to leave in forces towards Egypt, attempting its conquest, in order to cut off the direct connection from England and the Indies.

The French fleet, which carried the Armée d'Orient to Egypt, left on May 19, 1798, taking with them 167 scientists of different disciplines and artists.

Buonaparte's aim was to have them make the "great inventory of the Nile Valley", until then almost unknown and handed down only by the written memories of a small number of travellers.

We’ll omit other pages, about the military history of the Egyptian campaign, and focus our attention on the scientific results of the expedition, that led to interesting discoveries.

The group of scientists , put at the service of the newborn “Institut d'Egypte” - based on the model of the “Institut de France” - were called by the soldiers “savants” (literally “wise men”), and they reproduced, with plenty of details, hundreds of objects and monuments, collecting an enormous amount of informations and data.

In September 1798, Napoleon went with some Savants to Giza, to observe closely and climb the great pyramid of Cheops, which only later will be studied in depth.

In November 1798, Vivant Denon, engraver and writer (later made baron and the first organizer of the Louvre Museum) left for the Upper Egypt in the wake of General Desaix's 21st brigade; during the brief stops, he feverishly drew and noted down everything of interest to him; in the first thirty years of the 19th century, these drawings will be included in the text volumes and tables of the "Description de l'Egypte" which, in the years to come, will be used as a model for the famous French ceramics of Sèvres (the famous Egyptian service, Napoleon's divorce gift to Josephine on which Denon's landscapes were reproduced) and later used to produce jewels with an oriental taste by the most famous French jewellers.

The work, made on special paper and in an unusual format, was published in a first edition between 1810 and 1826 and was dedicated to Napoleon, so much so that it was called "Imperial Edition".

In the meantime, the military situation became increasingly critical. Napoleon secretly returned to France in August 1799, gradually followed by the scientists from the Institut d'Egypte.

In the second half of July 1799, Lieutenant Pierre Francoise Xavier Bouchard discovered by chance, among the filling material of a fort near Rosetta, a block of black stone engraved with signs of different writings, weighing 762 kg, which had evidently been removed from an ancient building.

The French immediately realized the importance of this object, and decided to transfer it to the Institut d'Egypte, where the experts were to question themselves at length about the writings that appeared there: the first one at the top is in hieroglyphic, the central one in demotic (a cursive writing spread in Egypt during the 7th century BC), and the one at the bottom in Greek. The "Rosetta stele", as it would later be called, was the most important discovery of the French expedition, but it was only in 1822, after several attempts by various English scholars, that Jean Francois Champollion succeeded in deciphering it, laying the foundations for understanding the civilization of ancient Egypt and the outbreak, especially in France, of Egyptomania. The text of the stele was written by the priests gathered in Menfi, to celebrate the coronation of Ptolemy V Epiphanies (196 B.C.) and proclaim the official cult of the sovereign god in all the temples of the Reign.

The departure of the Savants from Egypt was not without difficulties, some of them, who survived the plague, even after the landing of the English army on March 8, 1801, managed to leave with all their materials on August 9. Others, instead, who had headed to Alexandria, remained stuck in the city for five months, hostages of the greed of the English, led by General Hutchinson, who wanted to take possession of all the material collected by the “savants”, considering it spoils of war, raising the protests of the French delegation composed of the naturalists Savigny and Saint-Hilaire who had come to defend the product of their work.

Although under threat of being taken prisoner, Saint-Hilaire decided to make a final attempt, concluding his speech with these famous words: "No, we will not obey! We will burn out our own riches. It's the celebrity you're aiming at. Well, rest assured that history will remind you: you too will have burned down a library in Alexandria!".

At that point the English gave in, albeit partially, and French scholars were allowed to take with them only medium sized artifacts and personal documents; they were thus forced to abandon everything else including the famous Rosetta stele, still nowadays preserved at the British Museum in London.

I mean, even if the Egyptian expedition didn't make its mark in military history, it succeeded in the discovery of a past... that otherwise would have been lost.

Commenti e 'mi piace' / comments and likes on:

https://www.facebook.com/playinghistorysite/posts/2705478096166335?__tn__=K-R

https://www.facebook.com/playinghistorysite/posts/2705598486154296?__tn__=K-R